I have always congratulated myself on having the good sense to be born and raised in nominally weather-safe locations in North Jersey (read: Not the Jersey Shore), and, thereafter, on moving from one nominally weather-safe location to another.

In upstate New York, for instance, we were well north of major rainstorm territory, just south of major blizzard territory, some fifteen hundred miles east of major tornado territory, and some three thousand miles east of major earthquake territory.

Yes, you’re right. An earthquake is not a weather event. But when one is flailing about, grasping at minutiae upon which to congratulate oneself, does it matter?

To put a finer point on it, not once have my wife and I bought a house in a one-hundred-year flood plain.

But now, we live in a house that sits in a flood plain wherever we tie her up.

And now, we are facing our new home’s first threat.

What was I thinking?

Joaquin

On Monday, in an area several hundred miles northeast of the Bahamas, the Atlantic Ocean gave birth to a bouncing baby tropical storm that the World Meteorological Organization christened Joaquin.

Just four days later, Joaquin is all grown up. This morning, he is a Category 4 hurricane, reaching out from his 133 mph core to pound the Central Bahamas.

According to this morning’s early news, Joaquin has so far appeared to be more a vandal than a murderer; the Bahamas National Emergency Management Agency had not yet received any reports of fatalities or injuries attributable to him. That there should be no such reports coming out from under a Category 4 hurricane is both a miracle and a testament to the accumulated weather wisdom of the Bahamian people.

But it’s not over yet. Bahamian officials also reported that some people remain trapped in flooded homes, and that they lost communication with a couple of islands overnight.

And East Coast Americans do not seem to have accumulated the same wisdom. Weather.com reports that a person was killed near Spartanburg, South Carolina in a vehicle submerged in flood waters, waters attributed not to Joaquin but rather to the heavy rains our forecasters have been warning us about for days.

So pray for the continued survival of the Bahamian people. And pray also that the rest of us get smarter. Because Joaquin, like many of his siblings, is expected to head north soon.

The Cone of Uncertainty

People along the U.S. East Coast have been tensely watching the National Hurricane Center (NHC) forecast Joaquin’s next moves for a few days now.

In particular, we have been consumed by one particular graphic tool known as the cone of uncertainty. Brian McNoldy, writing for the Washington Post’s Capital Weather Gang, describes it as “the cone that surrounds the main track line and gives a range of possibilities for the storm’s future path.”

In short, it’s the NHC’s best guess as to where the center of a storm might–repeat–might end up in the next few days.

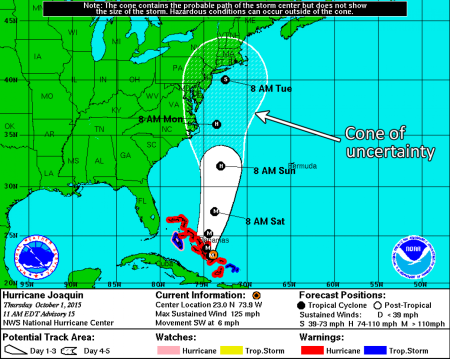

Sometime yesterday, the graphic looked like this.

And this morning, it looked like this.

The second graphic tells us that the storm the NHC once believed could make landfall somewhere on the East Coast is now expected to pass us at sea. That is nominally good news; and we, the graphics-consuming public who have come to rely on such marvelous pictures as we assess what all this means for us, are greatly comforted indeed.

But let’s not get too comfortable just yet.

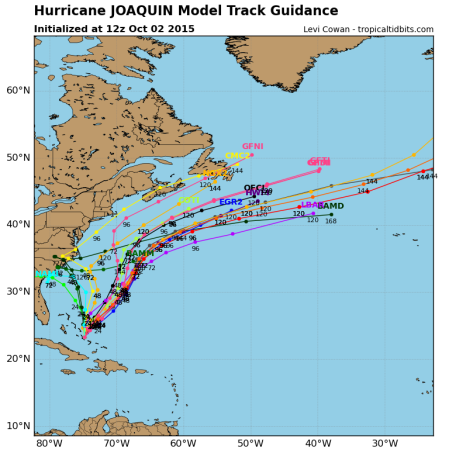

The cone of uncertainty is, apparently, just an amalgamation of several different storm track prediction models, each of which weighs different atmosphere conditions that could affect the track differently. (What else could it be, after all?) And the atmospheric conditions facing forecasters as they try to predict Joaquin have reportedly been somewhat more variable and complex than they usually have to deal with.

As a result, the individual models from which the cone of uncertainly is constructed are far from achieving a consensus about Joaquin’s track. And Mr. McNoldy goes on to report that the NHC has drawn criticism for not reflecting this increased unpredictability in the algorithms that produce the cone of uncertainty.

The spaghetti plot shown above, apparently produced this morning, makes his point. Of the fifteen or so possible tracks shown in it, seven veer back toward the East Coast. And four of these make landfall between South Carolina and Georgia.

Not having been born and raised a meterologist, I am in no position to pass judgment on the work of the NHC.

I am just a member of the aforementioned public who has come to rely on such pictures. And thanks to Mr. McNolty’s reporting, I just felt my comfort zone shrink beneath my bottom. So it’s time to get up and do. . . something.

Preparing for a hurricane

Yesterday, after reviewing some hurricane prep web links provided by Commuter Cruiser and other sources, we began to prepare for Joaquin’s potential wind impact.

Reducing a boat’s windage essentially means removing and stowing any item on her exterior that, in catching the wind, might itself be subject to wind damage or might put excessive force on the boat’s structure. We started yesterday by taking down our roller furling jib, our staysail, our bimini canvas, and several pieces of protective canvas. Still to come are the mainsail and its cover, our cockpit cushions, and the dodger canvas currently keeping the past few days’ occasionally intense rain out of our companionway.

Then there is Joaquin’s potential for storm surges. According to our research both on line and among the locals here at the Cambridge Municipal Yacht Marina, these could lift the water we are sitting in from three to eight feet.

So we’ll move next to our dock lines, the deploying of which is an art unto itself. Short lines would keep the boat off our docks and pilings, but might not let her rise and fall to ride extreme changes in the water level. Long lines would do the latter, but not the former. Springy lines would absorb the energy of the boat’s surging back and forth on heightened waves coming in from the Choptank River instead of jerking her to a stop, assuming again that they stopped her short of the docks and pilings. All this is a balancing act.

And then there’s the matter of the lines’ basic strength. Currently, we have just one line leading from each of our four primary docking cleats to the four corners of our slip. We’ll double them. And since age has probably drained the lines of some of their initial strength, we’ll probably go further than that. Assuming we can find strong places on our boat, such as the base of the mast, to tie off to.

Finally, we’ll keep an eye on the forecasts. Hauling out remains an option, but one which diminishes with each passing hour as boatyard workers struggle to keep previous commitments to those already on their haulout lists.

Will it be enough?

I have no idea how to answer this question. But we’ll go with what we think we know, adjust as best we can, and hope the middle of next week finds us still writing from the Cambridge Municipal Yacht Marina.

Meanwhile, I just might ask the buyer of our former home in upstate New York if she’s willing to rent out her basement.

________

IMAGE CREDITS

Yesterday’s cone of uncertainty: Retrieved 10/2/2015 from Washington Post.

This morning’s cone of uncertainty: Retrieved 10/2/2015 from Boat US.

This morning’s spaghetti plot: Retrieved 10/2/2015 from Mike’s Weather Page. (No relation to the author.)

Boats suspended from docks: Retrieved 10/2/2015 from Boat US.

Where are you staying if the hurricane hits? How are you all holding up? Stay warm, dry, and safe. I’m praying for you. Tomorrow is Shabbat so my prayers will be more intense in synagogue.

LikeLike

So far, so good. Our cabin is now about half-full of the stuff we removed from our deck, so it’s tighter down here than it was two days ago. But compared to those in the Bahamas, the Carolinas and elsewhere whose living rooms have been made tighter by six feet of water, we’re lucky.

The cone of uncertainty is now so far out to sea that even I can’t quite imagine getting hit at this point, although a sudden left turn like the one that brought Hurricane Sandy to the New York metro area in 2012 could make liars and fools out of us all. If that happens, it’s a short walk to relatives here in town; and we’ll see what’s left of Meander when it’s over.

Meanwhile, thank you for your prayers. If the current cone is correct, Bermuda is now on the train tracks; so please make them as far-reaching as possible.

LikeLike

Hurricanes are why I never want to move to the East Coast of Florida. Of course, I said I would never move to MO after the Nancy Cruzan end of life fiasco in this state, but, here I am. I’m much more prepared for the blizzards of MN and SD than for liquid water. I now live 1) at the edge of a flood plain, and 2) in the exact reach of the New Madrid fault – and yes, we had a small earthquake just the other day. Hoping and praying y’all stay safe and floating free but tethered during Joaquin’s turmoil. As for me, I want to retire back North before the Big One hits the Midwest.

LikeLike

Wow, an earthquake. I’d rather take my chances with. . . who am I kidding? I don’t want to take chances with any of them.

LikeLike

Normally I wouldn’t follow an east coast storm since we don’t know anyone back there and mostly they wash out, but I will be watching this one with deep concern. Stay safe. It sounds like you’re doing all you can to prepare. I like the saying if you prepare for an emergency, you don’t have one.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Take care. Good luck with your preparations.

LikeLiked by 1 person